Ebola virus disease

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia"Ebola" redirects here. For other uses, see Ebola (disambiguation).Ebola virus disease Classification and external resources  Two nurses standing near Mayinga N'Seka, a nurse with Ebola virus disease in the 1976 outbreak in Zaire. N'Seka died a few days later.

Two nurses standing near Mayinga N'Seka, a nurse with Ebola virus disease in the 1976 outbreak in Zaire. N'Seka died a few days later.ICD-10 A98.4 ICD-9 078.89 DiseasesDB 18043 MedlinePlus 001339 eMedicine med/626 MeSH D019142

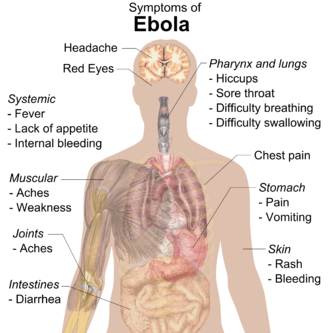

Ebola virus disease (EVD; also Ebola hemorrhagic fever, or EHF), or simply Ebola, is a disease of humans and other primatescaused by ebolaviruses. Signs and symptoms typically start between two days and three weeks after contracting the virus as a fever,sore throat, muscle pain, and headaches. Then, vomiting, diarrhea and rash usually follow, along with decreased function of the liverand kidneys. At this time some people begin to bleed both internally and externally.[1] The disease has a high risk of death, killing between 25 percent and 90 percent of those infected with the virus, averaging out at 50 percent.[1] This is often due to low blood pressure from fluid loss, and typically follows six to sixteen days after symptoms appear.[2]The virus spreads by direct contact with blood or other body fluids of an infected human or other animal.[1] Infection with the virus may also occur by direct contact with a recently contaminated item or surface.[1] Spread of the disease through the air has not been documented in the natural environment.[3] EBOV may be spread by semen or breast milk for several weeks to months after recovery.[1][4] African fruit bats are believed to be the normal carrier in nature, able to spread the virus without being affected by it. Humans become infected by contact with the bats or with a living or dead animal that has been infected by bats. After human infection occurs, the disease may also spread between people. Other diseases such as malaria, cholera, typhoid fever, meningitisand other viral hemorrhagic fevers may resemble EVD. Blood samples are tested for viral RNA, viral antibodies or for the virus itself to confirm the diagnosis.[1]Control of outbreaks requires coordinated medical services, along with a certain level of community engagement. The medical services include: rapid detection of cases of disease, contact tracing of those who have come into contact with infected individuals, quick access to laboratory services, proper care and management of those who are infected and proper disposal of the dead through cremation or burial.[1][5] Prevention includes limiting the spread of disease from infected animals to humans.[1] This may be done by handling potentially infected bush meat only while wearing protective clothing and by thoroughly cooking it before consumption.[1] It also includes wearing proper protective clothing and washing hands when around a person with the disease.[1]Samples of body fluids and tissues from people with the disease should be handled with special caution.[1]No specific treatment or vaccine for the virus is commercially available. Efforts to help those who are infected are supportive; they include either oral rehydration therapy (drinking slightly sweetened and salty water) or giving intravenous fluids as well as treating symptoms. This supportive care improves outcomes. EVD was first identified in 1976 in an area of Sudan (now part of South Sudan), and in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The disease typically occurs in outbreaks in tropical regions of sub-Saharan Africa.[1] Through 2013, the World Health Organization reported a total of 1,716 cases in 24 outbreaks.[1][6] The largest outbreak to date is the ongoing epidemic in West Africa, which is centered in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia.[7][8][9] As of 4 November 2014, this outbreak has 13,592 reported cases resulting in 5,408 deaths.[10][11][12][13]

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Ebola" redirects here. For other uses, see Ebola (disambiguation).

| Ebola virus disease | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Two nurses standing near Mayinga N'Seka, a nurse with Ebola virus disease in the 1976 outbreak in Zaire. N'Seka died a few days later. | |

| ICD-10 | A98.4 |

| ICD-9 | 078.89 |

| DiseasesDB | 18043 |

| MedlinePlus | 001339 |

| eMedicine | med/626 |

| MeSH | D019142 |

Ebola virus disease (EVD; also Ebola hemorrhagic fever, or EHF), or simply Ebola, is a disease of humans and other primatescaused by ebolaviruses. Signs and symptoms typically start between two days and three weeks after contracting the virus as a fever,sore throat, muscle pain, and headaches. Then, vomiting, diarrhea and rash usually follow, along with decreased function of the liverand kidneys. At this time some people begin to bleed both internally and externally.[1] The disease has a high risk of death, killing between 25 percent and 90 percent of those infected with the virus, averaging out at 50 percent.[1] This is often due to low blood pressure from fluid loss, and typically follows six to sixteen days after symptoms appear.[2]

The virus spreads by direct contact with blood or other body fluids of an infected human or other animal.[1] Infection with the virus may also occur by direct contact with a recently contaminated item or surface.[1] Spread of the disease through the air has not been documented in the natural environment.[3] EBOV may be spread by semen or breast milk for several weeks to months after recovery.[1][4] African fruit bats are believed to be the normal carrier in nature, able to spread the virus without being affected by it. Humans become infected by contact with the bats or with a living or dead animal that has been infected by bats. After human infection occurs, the disease may also spread between people. Other diseases such as malaria, cholera, typhoid fever, meningitisand other viral hemorrhagic fevers may resemble EVD. Blood samples are tested for viral RNA, viral antibodies or for the virus itself to confirm the diagnosis.[1]

Control of outbreaks requires coordinated medical services, along with a certain level of community engagement. The medical services include: rapid detection of cases of disease, contact tracing of those who have come into contact with infected individuals, quick access to laboratory services, proper care and management of those who are infected and proper disposal of the dead through cremation or burial.[1][5] Prevention includes limiting the spread of disease from infected animals to humans.[1] This may be done by handling potentially infected bush meat only while wearing protective clothing and by thoroughly cooking it before consumption.[1] It also includes wearing proper protective clothing and washing hands when around a person with the disease.[1]Samples of body fluids and tissues from people with the disease should be handled with special caution.[1]

No specific treatment or vaccine for the virus is commercially available. Efforts to help those who are infected are supportive; they include either oral rehydration therapy (drinking slightly sweetened and salty water) or giving intravenous fluids as well as treating symptoms. This supportive care improves outcomes. EVD was first identified in 1976 in an area of Sudan (now part of South Sudan), and in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The disease typically occurs in outbreaks in tropical regions of sub-Saharan Africa.[1] Through 2013, the World Health Organization reported a total of 1,716 cases in 24 outbreaks.[1][6] The largest outbreak to date is the ongoing epidemic in West Africa, which is centered in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia.[7][8][9] As of 4 November 2014, this outbreak has 13,592 reported cases resulting in 5,408 deaths.[10][11][12][13]

Contents

Signs and symptoms

The length of time between exposure to the virus and the development of symptoms of the disease is usually 2 to 21 days.[1][14]Symptoms usually begin with a sudden influenza-like stage characterized by feeling tired, fever, pain in the muscles and joints, headache, and sore throat.[1][15][16] The fever is usually higher than 38.3 °C (100.9 °F).[17] This is often followed by vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain.[16] Next, shortness of breath and chest pain may occur, along with swelling, headaches and confusion.[16] In about half of the cases, the skin may develop a maculopapular rash (a flat red area covered with small bumps).[17]In some cases, internal and external bleeding may occur.[1] This typically begins five to seven days after the first symptoms.[18] All infected people show some decreased blood clotting.[17] Bleeding from mucous membranes or from sites of needle punctures has been reported in 40–50 percent of cases.[19] This may result in the vomiting of blood, coughing up of blood or blood in stool.[20] Bleeding into the skin may create petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses or hematomas (especially around needle injection sites).[21] Bleeding into the whites of the eyes may also occur. Heavy bleeding is uncommon, and if it occurs, it is usually located within the gastrointestinal tract.[17][22]Recovery may begin between 7 and 14 days after the start of symptoms.[16] Death, if it occurs, follows typically 6 to 16 days from the start of symptoms and is often due to low blood pressure from fluid loss.[2] In general, bleeding often indicates a worse outcome, and this blood loss may result in death.[15] People are often in a coma near the end of life.[16] Those who survive often have ongoing muscle and joint pain, liver inflammation, and decreased hearing among other difficulties.[16]

The length of time between exposure to the virus and the development of symptoms of the disease is usually 2 to 21 days.[1][14]

Symptoms usually begin with a sudden influenza-like stage characterized by feeling tired, fever, pain in the muscles and joints, headache, and sore throat.[1][15][16] The fever is usually higher than 38.3 °C (100.9 °F).[17] This is often followed by vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain.[16] Next, shortness of breath and chest pain may occur, along with swelling, headaches and confusion.[16] In about half of the cases, the skin may develop a maculopapular rash (a flat red area covered with small bumps).[17]

In some cases, internal and external bleeding may occur.[1] This typically begins five to seven days after the first symptoms.[18] All infected people show some decreased blood clotting.[17] Bleeding from mucous membranes or from sites of needle punctures has been reported in 40–50 percent of cases.[19] This may result in the vomiting of blood, coughing up of blood or blood in stool.[20] Bleeding into the skin may create petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses or hematomas (especially around needle injection sites).[21] Bleeding into the whites of the eyes may also occur. Heavy bleeding is uncommon, and if it occurs, it is usually located within the gastrointestinal tract.[17][22]

Recovery may begin between 7 and 14 days after the start of symptoms.[16] Death, if it occurs, follows typically 6 to 16 days from the start of symptoms and is often due to low blood pressure from fluid loss.[2] In general, bleeding often indicates a worse outcome, and this blood loss may result in death.[15] People are often in a coma near the end of life.[16] Those who survive often have ongoing muscle and joint pain, liver inflammation, and decreased hearing among other difficulties.[16]

Cause

Main articles: Ebolavirus (taxonomic group) and Ebola virus (specific virus)EVD in humans is caused by four of five viruses of the genus Ebolavirus. The four are Bundibugyo virus (BDBV), Sudan virus (SUDV), Taï Forest virus (TAFV) and one simply called Ebola virus (EBOV, formerly Zaire Ebola virus).[23] EBOV is the only member of the Zaire ebolavirus species and the most dangerous of the known EVD-causing viruses, and is responsible for the largest number of outbreaks.[24] The fifth virus, Reston virus (RESTV), is not thought to cause disease in humans, but has caused disease in other primates.[25][26] All five viruses are closely related to marburgviruses.[23]

Main articles: Ebolavirus (taxonomic group) and Ebola virus (specific virus)

EVD in humans is caused by four of five viruses of the genus Ebolavirus. The four are Bundibugyo virus (BDBV), Sudan virus (SUDV), Taï Forest virus (TAFV) and one simply called Ebola virus (EBOV, formerly Zaire Ebola virus).[23] EBOV is the only member of the Zaire ebolavirus species and the most dangerous of the known EVD-causing viruses, and is responsible for the largest number of outbreaks.[24] The fifth virus, Reston virus (RESTV), is not thought to cause disease in humans, but has caused disease in other primates.[25][26] All five viruses are closely related to marburgviruses.[23]

Transmission

Between people, Ebola disease spreads only by direct contact with the blood or body fluids of a person who has developed symptoms of the disease.[27][28][29] Body fluids that may contain ebolaviruses include saliva, mucus, vomit, feces, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine and semen.[30] The WHO states that only people who are very sick are able to spread Ebola disease in saliva, and whole virus has not been reported to be transmitted through sweat. Most people spread the virus through blood, feces and vomit.[31] Entry points for the virus include the nose, mouth, eyes, open wounds, cuts and abrasions.[30] Ebola may be spread through largedroplets; however, this is believed to occur only when a person is very sick.[32] This can happen if a person is splashed with droplets.[32] Contact with surfaces or objects contaminated by the virus, particularly needles and syringes, may also transmit the infection.[33][34] The virus is able to survive on objects for a few hours in a dried state and can survive for a few days within body fluids.[30]The Ebola virus may be able to persist for up to 7 weeks in the semen of survivors after they recovered, which could lead to infections via sexual intercourse.[1] Ebola may also occur in the breast milk of women after recovery, and it is not known when it is safe to breastfeed again.[4] Otherwise, people who have recovered are not infectious.[33]The potential for widespread infections in countries with medical systems capable of observing correct medical isolation procedures is considered low.[35] Usually when someone has symptoms of the disease, they are unable to travel without assistance.[36]Dead bodies remain infectious; thus, people handling human remains in practices such as traditional burial rituals or more modern processes such as embalming are at risk.[35]60% of the cases of Ebola infections in Guinea during the 2014 outbreak are believed to have been contracted via unprotected (or unsuitably protected) contact with infected corpses during certain Guinean burial rituals.[37][38]Health-care workers treating those who are infected are at greatest risk of getting infected themselves.[33] The risk increases when these workers do not have appropriate protective clothing such as masks, gowns, gloves and eye protection; do not wear it properly; or handle contaminated clothing incorrectly.[33] This risk is particularly common in parts of Africa where health systems function poorly and where the disease mostly occurs.[39] Hospital-acquired transmission has also occurred in some African countries resulting from the reuse of needles.[40][41] Some health-care centers caring for people with the disease do not have running water.[42] In the United States the spread to two medial workers treating an infected patients prompted criticism of inadequate training and procedures.[43]Human to human transmission of EBOV through the air has not been reported to occur during EVD outbreaks[3] and airborne transmission has only been demonstrated in very strict laboratory conditions in non-human primates.[27][34] The apparent lack of airborne transmission among humans may be due to levels of the virus in the lungs that are insufficient to cause new infections.[44] Spread of EBOV by water or food, other than bushmeat, has also not been observed.[33][34] No spread by mosquitos or other insects has been reported.[33]

Between people, Ebola disease spreads only by direct contact with the blood or body fluids of a person who has developed symptoms of the disease.[27][28][29] Body fluids that may contain ebolaviruses include saliva, mucus, vomit, feces, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine and semen.[30] The WHO states that only people who are very sick are able to spread Ebola disease in saliva, and whole virus has not been reported to be transmitted through sweat. Most people spread the virus through blood, feces and vomit.[31] Entry points for the virus include the nose, mouth, eyes, open wounds, cuts and abrasions.[30] Ebola may be spread through largedroplets; however, this is believed to occur only when a person is very sick.[32] This can happen if a person is splashed with droplets.[32] Contact with surfaces or objects contaminated by the virus, particularly needles and syringes, may also transmit the infection.[33][34] The virus is able to survive on objects for a few hours in a dried state and can survive for a few days within body fluids.[30]

The Ebola virus may be able to persist for up to 7 weeks in the semen of survivors after they recovered, which could lead to infections via sexual intercourse.[1] Ebola may also occur in the breast milk of women after recovery, and it is not known when it is safe to breastfeed again.[4] Otherwise, people who have recovered are not infectious.[33]

The potential for widespread infections in countries with medical systems capable of observing correct medical isolation procedures is considered low.[35] Usually when someone has symptoms of the disease, they are unable to travel without assistance.[36]

Dead bodies remain infectious; thus, people handling human remains in practices such as traditional burial rituals or more modern processes such as embalming are at risk.[35]60% of the cases of Ebola infections in Guinea during the 2014 outbreak are believed to have been contracted via unprotected (or unsuitably protected) contact with infected corpses during certain Guinean burial rituals.[37][38]

Health-care workers treating those who are infected are at greatest risk of getting infected themselves.[33] The risk increases when these workers do not have appropriate protective clothing such as masks, gowns, gloves and eye protection; do not wear it properly; or handle contaminated clothing incorrectly.[33] This risk is particularly common in parts of Africa where health systems function poorly and where the disease mostly occurs.[39] Hospital-acquired transmission has also occurred in some African countries resulting from the reuse of needles.[40][41] Some health-care centers caring for people with the disease do not have running water.[42] In the United States the spread to two medial workers treating an infected patients prompted criticism of inadequate training and procedures.[43]

Human to human transmission of EBOV through the air has not been reported to occur during EVD outbreaks[3] and airborne transmission has only been demonstrated in very strict laboratory conditions in non-human primates.[27][34] The apparent lack of airborne transmission among humans may be due to levels of the virus in the lungs that are insufficient to cause new infections.[44] Spread of EBOV by water or food, other than bushmeat, has also not been observed.[33][34] No spread by mosquitos or other insects has been reported.[33]

Initial case

Although it is not entirely clear how Ebola initially spreads from animals to humans, the spread is believed to involve direct contact with an infected wild animal or fruit bat.[33] Besides bats, other wild animals sometimes infected with EBOV include several monkey species, chimpanzees, gorillas, baboons and duikers.[48]Animals may become infected when they eat fruit partially eaten by bats carrying the virus.[49] Fruit production, animal behavior and other factors may trigger outbreaks among animal populations.[49]Evidence indicates that both domestic dogs and pigs can also be infected with EBOV.[50] Dogs do not appear to develop symptoms when they carry the virus, and pigs appear to be able to transmit the virus to at least some primates.[50] Although some dogs in an area in which a human outbreak occurred had antibodies to EBOV, it is unclear whether they played a role in spreading the disease to people.[50]

Although it is not entirely clear how Ebola initially spreads from animals to humans, the spread is believed to involve direct contact with an infected wild animal or fruit bat.[33] Besides bats, other wild animals sometimes infected with EBOV include several monkey species, chimpanzees, gorillas, baboons and duikers.[48]

Animals may become infected when they eat fruit partially eaten by bats carrying the virus.[49] Fruit production, animal behavior and other factors may trigger outbreaks among animal populations.[49]

Evidence indicates that both domestic dogs and pigs can also be infected with EBOV.[50] Dogs do not appear to develop symptoms when they carry the virus, and pigs appear to be able to transmit the virus to at least some primates.[50] Although some dogs in an area in which a human outbreak occurred had antibodies to EBOV, it is unclear whether they played a role in spreading the disease to people.[50]

Reservoir

The natural reservoir for Ebola has yet to be confirmed; however, bats are considered to be the most likely candidate species.[34] Three types of fruit bats (Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti and Myonycteris torquata) were found to possibly carry the virus without getting sick.[51] As of 2013, whether other animals are involved in its spread is not known.[50] Plants, arthropods and birds have also been considered possible viral reservoirs.[1]Bats were known to roost in the cotton factory in which the first cases of the 1976 and 1979 outbreaks were observed, and they have also been implicated in Marburg virus infections in 1975 and 1980.[52] Of 24 plant and 19 vertebrate species experimentally inoculated with EBOV, only bats became infected.[53] The bats displayed no clinical signs of disease, which is considered evidence that these bats are a reservoir species of EBOV. In a 2002–2003 survey of 1,030 animals including 679 bats from Gabon and the Republic of the Congo, 13 fruit bats were found to contain EBOV RNA.[54] Antibodies against Zaire and Reston viruses have been found in fruit bats in Bangladesh, suggesting that these bats are also potential hosts of the virus and that the filoviruses are present in Asia.[55]Between 1976 and 1998, in 30,000 mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and arthropods sampled from regions of EBOV outbreaks, no Ebola virus was detected apart from some genetic traces found in six rodents (belonging to the species Mus setulosus and Praomys) and one shrew (Sylvisorex ollula) collected from the Central African Republic.[52][56] However, further research efforts have not confirmed rodents as a reservoir.[57] Traces of EBOV were detected in the carcasses of gorillas and chimpanzees during outbreaks in 2001 and 2003, which later became the source of human infections. However, the high rates of death in these species resulting from EBOV infection make it unlikely that these species represent a natural reservoir for the virus.[52]

The natural reservoir for Ebola has yet to be confirmed; however, bats are considered to be the most likely candidate species.[34] Three types of fruit bats (Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti and Myonycteris torquata) were found to possibly carry the virus without getting sick.[51] As of 2013, whether other animals are involved in its spread is not known.[50] Plants, arthropods and birds have also been considered possible viral reservoirs.[1]

Bats were known to roost in the cotton factory in which the first cases of the 1976 and 1979 outbreaks were observed, and they have also been implicated in Marburg virus infections in 1975 and 1980.[52] Of 24 plant and 19 vertebrate species experimentally inoculated with EBOV, only bats became infected.[53] The bats displayed no clinical signs of disease, which is considered evidence that these bats are a reservoir species of EBOV. In a 2002–2003 survey of 1,030 animals including 679 bats from Gabon and the Republic of the Congo, 13 fruit bats were found to contain EBOV RNA.[54] Antibodies against Zaire and Reston viruses have been found in fruit bats in Bangladesh, suggesting that these bats are also potential hosts of the virus and that the filoviruses are present in Asia.[55]

Between 1976 and 1998, in 30,000 mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and arthropods sampled from regions of EBOV outbreaks, no Ebola virus was detected apart from some genetic traces found in six rodents (belonging to the species Mus setulosus and Praomys) and one shrew (Sylvisorex ollula) collected from the Central African Republic.[52][56] However, further research efforts have not confirmed rodents as a reservoir.[57] Traces of EBOV were detected in the carcasses of gorillas and chimpanzees during outbreaks in 2001 and 2003, which later became the source of human infections. However, the high rates of death in these species resulting from EBOV infection make it unlikely that these species represent a natural reservoir for the virus.[52]

Virology

Main articles: Ebolavirus (taxonomic group) and Ebola virus (specific virus)Ebolaviruses contain single-stranded, non-infectious RNA genomes.[58] Ebolavirus genomes are approximately 19 kilobase pairs long and contain seven genes in the order 3'-UTR-NP-VP35-VP40-GP-VP30-VP24-L-5'-UTR.[59] The genomes of the five different ebolaviruses (BDBV, EBOV, RESTV, SUDV and TAFV) differ in sequence and the number and location of gene overlaps. As all filoviruses, ebolavirions are filamentous particles that may appear in the shape of a shepherd's crook, of a "U" or of a "6," and they may be coiled, toroid or branched.[59] In general, ebolavirions are 80 nanometers (nm) in width and may be as long as 14,000 nm.[60]Their life cycle begins with a virion attaching to specific cell-surface receptors, followed by fusion of the virion envelope with cellular membranes and the concomitant release of the virus nucleocapsid into the cytosol. Ebolavirus' structural glycoprotein (known as GP1,2) is responsible for the virus' ability to bind to and infect targeted cells.[61] The viral RNA polymerase, encoded by the L gene, partially uncoats the nucleocapsid and transcribes the genes into positive-strand mRNAs, which are then translated into structural and nonstructural proteins. The most abundant protein produced is the nucleoprotein, whose concentration in the host cell determines when L switches from gene transcription to genome replication. Replication of the viral genome results in full-length, positive-strand antigenomes that are, in turn, transcribed into genome copies of negative-strand virus progeny. Newly synthesized structural proteins and genomes self-assemble and accumulate near the inside of the cell membrane. Virions bud off from the cell, gaining their envelopes from the cellular membrane from which they bud from. The mature progeny particles then infect other cells to repeat the cycle. The genetics of the Ebola virus are difficult to study because of EBOV's virulent characteristics.[62]

Main articles: Ebolavirus (taxonomic group) and Ebola virus (specific virus)

Ebolaviruses contain single-stranded, non-infectious RNA genomes.[58] Ebolavirus genomes are approximately 19 kilobase pairs long and contain seven genes in the order 3'-UTR-NP-VP35-VP40-GP-VP30-VP24-L-5'-UTR.[59] The genomes of the five different ebolaviruses (BDBV, EBOV, RESTV, SUDV and TAFV) differ in sequence and the number and location of gene overlaps. As all filoviruses, ebolavirions are filamentous particles that may appear in the shape of a shepherd's crook, of a "U" or of a "6," and they may be coiled, toroid or branched.[59] In general, ebolavirions are 80 nanometers (nm) in width and may be as long as 14,000 nm.[60]

Their life cycle begins with a virion attaching to specific cell-surface receptors, followed by fusion of the virion envelope with cellular membranes and the concomitant release of the virus nucleocapsid into the cytosol. Ebolavirus' structural glycoprotein (known as GP1,2) is responsible for the virus' ability to bind to and infect targeted cells.[61] The viral RNA polymerase, encoded by the L gene, partially uncoats the nucleocapsid and transcribes the genes into positive-strand mRNAs, which are then translated into structural and nonstructural proteins. The most abundant protein produced is the nucleoprotein, whose concentration in the host cell determines when L switches from gene transcription to genome replication. Replication of the viral genome results in full-length, positive-strand antigenomes that are, in turn, transcribed into genome copies of negative-strand virus progeny. Newly synthesized structural proteins and genomes self-assemble and accumulate near the inside of the cell membrane. Virions bud off from the cell, gaining their envelopes from the cellular membrane from which they bud from. The mature progeny particles then infect other cells to repeat the cycle. The genetics of the Ebola virus are difficult to study because of EBOV's virulent characteristics.[62]

Pathophysiology

Similar to other filoviridae, EBOV replicates very efficiently in many cells, producing large amounts of virus in monocytes, macrophages,dendritic cells and other cells. Replication of the virus in monocytes triggers the release of high levels of inflammatory chemical signals.[63]EBOV is thought to infect humans through contact with mucous membranes or through skin breaks.[27] Once infected, endothelial cells(cells lining the inside of blood vessels), liver cells, and several types of immune cells such as macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells are the main targets of infection.[27] Following infection with the virus, the immune cells carry the virus to nearby lymph nodes where further reproduction of the virus takes place.[27] From there, the virus can enter the bloodstream and lymphatic system and spread throughout the body.[27] Macrophages are the first cells infected with the virus, and this infection results in programmed cell death.[60]Other types of white blood cells, such as lymphocytes, also undergo programmed cell death leading to an abnormally low concentration of lymphocytes in the blood.[27] This contributes to the weakened immune response seen in those infected with EBOV.[27]Filoviral infection also interferes with proper functioning of the innate immune system.[64] EBOV proteins blunt the human immune system's response to viral infections by interfering with the cells' ability to produce and respond to interferon proteins such as interferon-alpha, interferon-beta, and interferon gamma.[61][65]The VP24 and VP35 structural proteins of EBOV play a key role in this interference. When a cell is infected with EBOV, receptors located in the cell's cytosol (such as RIG-I and MDA5) or outside of the cytosol (such as Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9), recognize infectious molecules associated with the virus.[61] On TLR activation, proteins including interferon regulatory factor 3 andinterferon regulatory factor 7 trigger a signaling cascade that leads to the expression of type 1 interferons.[61] The type 1 interferons are then released and bind to the IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 receptors expressed on the surface of a neighboring cell.[61] Once interferon has bound to its receptors on the neighboring cell, the signaling proteins STAT1 and STAT2 are activated and move to the cell's nucleus.[61]This triggers the expression of interferon-stimulated genes, which code for proteins with antiviral properties.[61] EBOV's V24 protein blocks the production of these antiviral proteins by preventing the STAT1 signaling protein in the neighboring cell from entering the nucleus.[61] The VP35 protein directly inhibits the production of interferon-beta.[65] By inhibiting these immune responses, EBOV may quickly spread throughout the body.[60]Endothelial cells may be infected within 3 days after exposure to the virus.[60] The breakdown of endothelial cells leading to vascular injury can be attributed to EBOVglycoproteins. The widespread hemorrhage that occurs in affected people causes edema and hypovolemic shock.[63] After infection, a secreted glycoprotein, small soluble glycoprotein (sGP) (or Ebola virus glycoprotein [GP]), is synthesized. EBOV replication overwhelms protein synthesis of infected cells and the host immune defenses. The GP forms a trimeric complex, which tethers the virus to the endothelial cells. The sGP forms a dimeric protein that interferes with the signaling of neutrophils, another type of white blood cell, which enables the virus to evade the immune system by inhibiting early steps of neutrophil activation.The presence of viral particles and the cell damage resulting from viruses budding out of the cell causes the release of chemical signals (such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8), which are molecular signals for fever and inflammation. The damage to human cells, caused by infection of the endothelial cells, decreases the integrity of blood vessels. This loss of vascular integrity increases with the synthesis of GP, which reduces the availability of specific integrins responsible for cell adhesion to the intercellular structure and causes damage to the liver, leading to improper clotting.[66]

Similar to other filoviridae, EBOV replicates very efficiently in many cells, producing large amounts of virus in monocytes, macrophages,dendritic cells and other cells. Replication of the virus in monocytes triggers the release of high levels of inflammatory chemical signals.[63]

EBOV is thought to infect humans through contact with mucous membranes or through skin breaks.[27] Once infected, endothelial cells(cells lining the inside of blood vessels), liver cells, and several types of immune cells such as macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells are the main targets of infection.[27] Following infection with the virus, the immune cells carry the virus to nearby lymph nodes where further reproduction of the virus takes place.[27] From there, the virus can enter the bloodstream and lymphatic system and spread throughout the body.[27] Macrophages are the first cells infected with the virus, and this infection results in programmed cell death.[60]Other types of white blood cells, such as lymphocytes, also undergo programmed cell death leading to an abnormally low concentration of lymphocytes in the blood.[27] This contributes to the weakened immune response seen in those infected with EBOV.[27]

Filoviral infection also interferes with proper functioning of the innate immune system.[64] EBOV proteins blunt the human immune system's response to viral infections by interfering with the cells' ability to produce and respond to interferon proteins such as interferon-alpha, interferon-beta, and interferon gamma.[61][65]

The VP24 and VP35 structural proteins of EBOV play a key role in this interference. When a cell is infected with EBOV, receptors located in the cell's cytosol (such as RIG-I and MDA5) or outside of the cytosol (such as Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9), recognize infectious molecules associated with the virus.[61] On TLR activation, proteins including interferon regulatory factor 3 andinterferon regulatory factor 7 trigger a signaling cascade that leads to the expression of type 1 interferons.[61] The type 1 interferons are then released and bind to the IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 receptors expressed on the surface of a neighboring cell.[61] Once interferon has bound to its receptors on the neighboring cell, the signaling proteins STAT1 and STAT2 are activated and move to the cell's nucleus.[61]This triggers the expression of interferon-stimulated genes, which code for proteins with antiviral properties.[61] EBOV's V24 protein blocks the production of these antiviral proteins by preventing the STAT1 signaling protein in the neighboring cell from entering the nucleus.[61] The VP35 protein directly inhibits the production of interferon-beta.[65] By inhibiting these immune responses, EBOV may quickly spread throughout the body.[60]

Endothelial cells may be infected within 3 days after exposure to the virus.[60] The breakdown of endothelial cells leading to vascular injury can be attributed to EBOVglycoproteins. The widespread hemorrhage that occurs in affected people causes edema and hypovolemic shock.[63] After infection, a secreted glycoprotein, small soluble glycoprotein (sGP) (or Ebola virus glycoprotein [GP]), is synthesized. EBOV replication overwhelms protein synthesis of infected cells and the host immune defenses. The GP forms a trimeric complex, which tethers the virus to the endothelial cells. The sGP forms a dimeric protein that interferes with the signaling of neutrophils, another type of white blood cell, which enables the virus to evade the immune system by inhibiting early steps of neutrophil activation.

The presence of viral particles and the cell damage resulting from viruses budding out of the cell causes the release of chemical signals (such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8), which are molecular signals for fever and inflammation. The damage to human cells, caused by infection of the endothelial cells, decreases the integrity of blood vessels. This loss of vascular integrity increases with the synthesis of GP, which reduces the availability of specific integrins responsible for cell adhesion to the intercellular structure and causes damage to the liver, leading to improper clotting.[66]

Diagnosis

When EVD is suspected in a person, his or her travel and work history, along with an exposure to wildlife, are important factors to consider for possible further medical examination.

When EVD is suspected in a person, his or her travel and work history, along with an exposure to wildlife, are important factors to consider for possible further medical examination.

Nonspecific laboratory testing

Possible laboratory indicators of EVD include a low platelet count; an initially decreased white blood cell count followed by an increased white blood cell count; elevated levels of the liver enzymes alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST); and abnormalities in blood clotting often consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) such as a prolonged prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and bleeding time.[67]

Possible laboratory indicators of EVD include a low platelet count; an initially decreased white blood cell count followed by an increased white blood cell count; elevated levels of the liver enzymes alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST); and abnormalities in blood clotting often consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) such as a prolonged prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and bleeding time.[67]

Specific laboratory testing

The diagnosis of EVD is confirmed by isolating the virus, detecting its RNA or proteins, or detecting antibodies against the virus in a person's blood. Isolating the virus by cell culture, detecting the viral RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and detecting proteins by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) are methods best used in the early stages of the disease and also for detecting the virus in human remains. Detecting antibodies against the virus is most reliable in the later stages of the disease and in those who recover.[68]During an outbreak, isolation of the virus via cell culture methods is often not feasible. In field or mobile hospitals, the most common and sensitive diagnostic methods are real-time PCR and ELISA.[69] In 2014, with new mobile testing facilities deployed in parts of Liberia, test results were obtained 3–5 hours after sample submission.[70]Filovirions, such as EBOV, may be identified by their unique filamentous shapes in cell cultures examined with electron microscopy, but this method cannot distinguish the various filoviruses.[71]

The diagnosis of EVD is confirmed by isolating the virus, detecting its RNA or proteins, or detecting antibodies against the virus in a person's blood. Isolating the virus by cell culture, detecting the viral RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and detecting proteins by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) are methods best used in the early stages of the disease and also for detecting the virus in human remains. Detecting antibodies against the virus is most reliable in the later stages of the disease and in those who recover.[68]

During an outbreak, isolation of the virus via cell culture methods is often not feasible. In field or mobile hospitals, the most common and sensitive diagnostic methods are real-time PCR and ELISA.[69] In 2014, with new mobile testing facilities deployed in parts of Liberia, test results were obtained 3–5 hours after sample submission.[70]

Filovirions, such as EBOV, may be identified by their unique filamentous shapes in cell cultures examined with electron microscopy, but this method cannot distinguish the various filoviruses.[71]

Differential diagnosis

Early symptoms of EVD may be similar to those of other diseases common in Africa, including malaria and dengue fever.[15] The symptoms are also similar to those of Marburg virus disease and other viral hemorrhagic fevers.[72]The complete differential diagnosis is extensive and requires consideration of many other infectious diseases such as typhoid fever, shigellosis, rickettsial diseases, cholera,sepsis, borreliosis, EHEC enteritis, leptospirosis, scrub typhus, plague, Q fever, candidiasis, histoplasmosis, trypanosomiasis, visceral leishmaniasis, measles and viral hepatitisamong others.[73]Non-infectious diseases that may result in symptoms similar to those of EVD include acute promyelocytic leukemia, hemolytic uremic syndrome, snake envenomation, clotting factor deficiencies/platelet disorders, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, Kawasaki disease and warfarin poisoning.[69][74][75][76]

Early symptoms of EVD may be similar to those of other diseases common in Africa, including malaria and dengue fever.[15] The symptoms are also similar to those of Marburg virus disease and other viral hemorrhagic fevers.[72]

The complete differential diagnosis is extensive and requires consideration of many other infectious diseases such as typhoid fever, shigellosis, rickettsial diseases, cholera,sepsis, borreliosis, EHEC enteritis, leptospirosis, scrub typhus, plague, Q fever, candidiasis, histoplasmosis, trypanosomiasis, visceral leishmaniasis, measles and viral hepatitisamong others.[73]

Non-infectious diseases that may result in symptoms similar to those of EVD include acute promyelocytic leukemia, hemolytic uremic syndrome, snake envenomation, clotting factor deficiencies/platelet disorders, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, Kawasaki disease and warfarin poisoning.[69][74][75][76]

Prevention

Main article: Prevention of viral hemorrhagic fever

Main article: Prevention of viral hemorrhagic fever

Infection control

People who care for those infected with the Ebola virus should wear protective clothing including masks, gloves, gowns and goggles.[77] The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommend that the protective gear leaves no skin exposed.[78]These measures are also recommended for those who may handle objects contaminated by an infected person's body fluids.[79] In 2014, the CDC began recommending that medical personnel receive training on the proper suit-up and removal of personal protective equipment (PPE); in addition, a designated person, appropriately trained in biosafety, should be watching each step of these procedures to ensure they are done correctly.[78] In Sierra Leone, the typical training period for the use of such safety equipment lasts approximately 12 days.[80]The infected person should be in barrier-isolation from other people.[77] All equipment, medical waste, patient waste and surfaces that may have come into contact with body fluids need to be disinfected.[79] During the 2014 outbreak, kits were put together to help families treat Ebola disease in their homes, which include protective clothing as well as chlorine powderand other cleaning supplies.[81] Education of those who provide care in these techniques, and the provision of such barrier-separation supplies has been a priority of Doctors Without Borders.[82]Ebolaviruses can be eliminated with heat (heating for 30 to 60 minutes at 60 °C or boiling for 5 minutes). To disinfectsurfaces, some lipid solvents such as some alcohol-based products, detergents, sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or calcium hypochlorite (bleaching powder), and other suitable disinfectants may be used at appropriate concentrations.[48][83]Education of the general public about the risk factors for Ebola infection and of the protective measures individuals may take to prevent infection is recommended by the World Health Organization.[1] These measures include avoiding direct contact with infected people and regular hand washing using soap and water.[84]Bushmeat, an important source of protein in the diet of some Africans, should be handled and prepared with appropriate protective clothing and thoroughly cooked before consumption.[1] Some research suggests that an outbreak of Ebola disease in the wild animals used for consumption may result in a corresponding human outbreak. Since 2003, such animal outbreaks have been monitored to predict and prevent Ebola outbreaks in humans.[85]If a person with Ebola disease dies, direct contact with the body should be avoided.[77] Certain burial rituals, which may have included making various direct contacts with a dead body, require reformulation such that they consistently maintain a proper protective barrier between the dead body and the living.[86][87][88] Social anthropologists may help find alternatives to traditional rules for burials.[89]Transportation crews are instructed to follow a certain isolation procedure should anyone exhibit symptoms resembling EVD.[90] As of August 2014, the WHO does not consider travel bans to be useful in decreasing spread of the disease.[36] In October 2014, the CDC defined four risk levels used to determine the level of 21-day monitoring for symptoms and restrictions on public activities.[91] In the United States, the CDC recommends that restrictions on public activity, including travel restrictions, are not required for the following defined risk levels:[91]- having been in a country with widespread Ebola disease transmission and having no known exposure (low risk); or having been in that country more than 21 days ago (no risk)

- encounter with a person showing symptoms; but not within 3 feet of the person with Ebola without wearing PPE; and no direct contact of body fluids

- having had brief skin contact with a person showing symptoms of Ebola disease when the person was believed to be not very contagious (low risk)

- in countries without widespread Ebola disease transmission: direct contact with a person showing symptoms of the disease while wearing PPE (low risk)

- contact with a person with Ebola disease before the person was showing symptoms (no risk).

The CDC recommends monitoring for the symptoms of Ebola disease for those both at "low risk" and at higher risk.[91]In laboratories where diagnostic testing is carried out, biosafety level 4-equivalent containment is required.[92] Laboratory researchers must be properly trained in BSL-4 practices and wear proper PPE.[92]

People who care for those infected with the Ebola virus should wear protective clothing including masks, gloves, gowns and goggles.[77] The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommend that the protective gear leaves no skin exposed.[78]These measures are also recommended for those who may handle objects contaminated by an infected person's body fluids.[79] In 2014, the CDC began recommending that medical personnel receive training on the proper suit-up and removal of personal protective equipment (PPE); in addition, a designated person, appropriately trained in biosafety, should be watching each step of these procedures to ensure they are done correctly.[78] In Sierra Leone, the typical training period for the use of such safety equipment lasts approximately 12 days.[80]

The infected person should be in barrier-isolation from other people.[77] All equipment, medical waste, patient waste and surfaces that may have come into contact with body fluids need to be disinfected.[79] During the 2014 outbreak, kits were put together to help families treat Ebola disease in their homes, which include protective clothing as well as chlorine powderand other cleaning supplies.[81] Education of those who provide care in these techniques, and the provision of such barrier-separation supplies has been a priority of Doctors Without Borders.[82]

Ebolaviruses can be eliminated with heat (heating for 30 to 60 minutes at 60 °C or boiling for 5 minutes). To disinfectsurfaces, some lipid solvents such as some alcohol-based products, detergents, sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or calcium hypochlorite (bleaching powder), and other suitable disinfectants may be used at appropriate concentrations.[48][83]Education of the general public about the risk factors for Ebola infection and of the protective measures individuals may take to prevent infection is recommended by the World Health Organization.[1] These measures include avoiding direct contact with infected people and regular hand washing using soap and water.[84]

Bushmeat, an important source of protein in the diet of some Africans, should be handled and prepared with appropriate protective clothing and thoroughly cooked before consumption.[1] Some research suggests that an outbreak of Ebola disease in the wild animals used for consumption may result in a corresponding human outbreak. Since 2003, such animal outbreaks have been monitored to predict and prevent Ebola outbreaks in humans.[85]

If a person with Ebola disease dies, direct contact with the body should be avoided.[77] Certain burial rituals, which may have included making various direct contacts with a dead body, require reformulation such that they consistently maintain a proper protective barrier between the dead body and the living.[86][87][88] Social anthropologists may help find alternatives to traditional rules for burials.[89]

Transportation crews are instructed to follow a certain isolation procedure should anyone exhibit symptoms resembling EVD.[90] As of August 2014, the WHO does not consider travel bans to be useful in decreasing spread of the disease.[36] In October 2014, the CDC defined four risk levels used to determine the level of 21-day monitoring for symptoms and restrictions on public activities.[91] In the United States, the CDC recommends that restrictions on public activity, including travel restrictions, are not required for the following defined risk levels:[91]

- having been in a country with widespread Ebola disease transmission and having no known exposure (low risk); or having been in that country more than 21 days ago (no risk)

- encounter with a person showing symptoms; but not within 3 feet of the person with Ebola without wearing PPE; and no direct contact of body fluids

- having had brief skin contact with a person showing symptoms of Ebola disease when the person was believed to be not very contagious (low risk)

- in countries without widespread Ebola disease transmission: direct contact with a person showing symptoms of the disease while wearing PPE (low risk)

- contact with a person with Ebola disease before the person was showing symptoms (no risk).

The CDC recommends monitoring for the symptoms of Ebola disease for those both at "low risk" and at higher risk.[91]

In laboratories where diagnostic testing is carried out, biosafety level 4-equivalent containment is required.[92] Laboratory researchers must be properly trained in BSL-4 practices and wear proper PPE.[92]

0 comments:

Post a Comment